If you’re like most people, odds are you’ve probably been told to “sit up straight” or “fix your posture” at some point in your lifetime. Adults commonly reprimand their children for slouching, and every day healthcare providers educate their patients on the importance of proper posture to decrease pain and prevent injury. Maintaining good posture does have benefits, such as improving blood flow, keeping nerves and blood vessels healthy, and conveying confidence to those around you, but do postural “impairments” really cause pain and lead to injury?

What is posture?

Posture is often defined as the “state of muscular and skeletal balance which protects supporting structures of the body against injury or progressive deformity”, regardless of the position someone is in. Ideal posture provides three benefits: maximum stability, minimal energy consumption, and minimal stress on anatomical structures.

There are two types of posture: static posture and dynamic posture. Static posture refers to how the body is aligned when standing, sitting, or lying down. In these positions body segments are fixed and muscle groups are coordinating to counteract gravity and other forces. This is what most people think about when they hear the term “posture”.

Dynamic posture is how the body is positioned during movement, such as walking, running, or lifting and carrying objects. During these tasks muscles are constantly adjusting to changes in position in order to move in the most efficient manner possible.

What is “ideal” posture, and why is it seen as important?

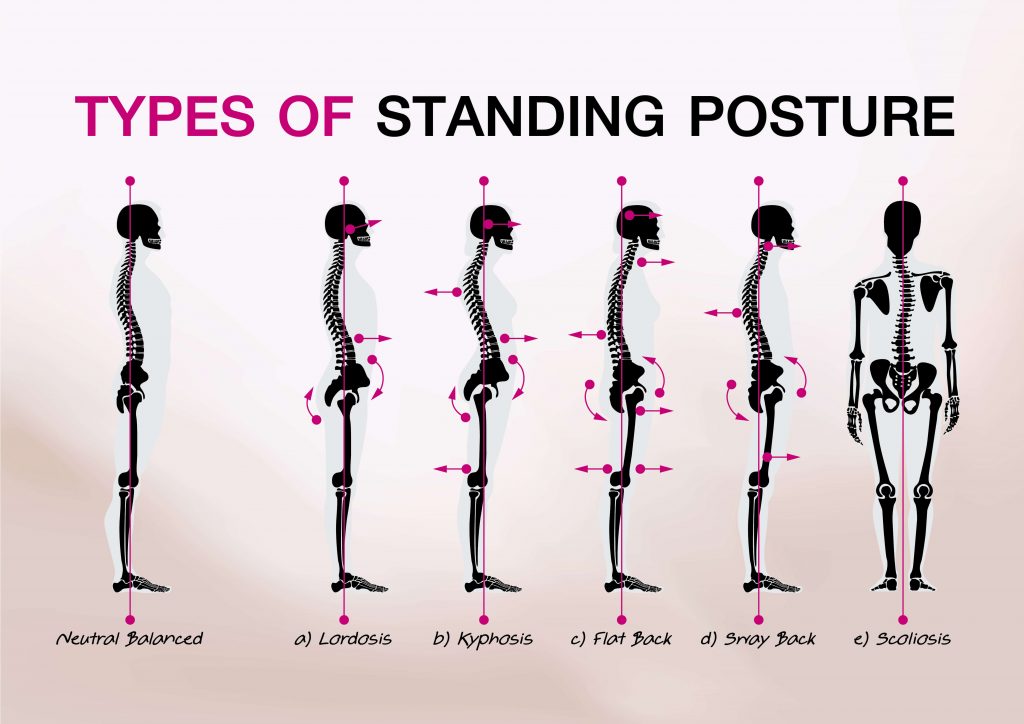

There is no true “gold standard” for what perfect posture is, but most medical professionals refer to images like the one above when assessing the static alignment of their patients. The general consensus is that there should be an imaginary straight line running through the earlobe, shoulder, center of the pelvis, greater trochanter (bony part of the femur on the outside of the hip), center of the knee joint, and just in front of the lateral malleolus (ankle bone). When viewed from the front or back, it’s theorized that both sides of the body should be perfectly symmetrical on either side of midline.

With this alignment, the body is properly balanced and optimal joint loading is achieved, meaning pressure is evenly distributed throughout the vertebrae, hips, knees, ankles, and feet, and muscles don’t have to work as hard to maintain the position. Impaired posture is present when one or more body segments lie outside of this imaginary line, placing more stress on joints and causing certain muscle groups to have to work harder to maintain balance. Theoretically, this is what leads to an increased probability of pain and dysfunction in the future.

In theory, this makes sense.

Common postural “impairments” and what the research really says

In reality, there’s an abundance of research that indicates postural deficits don’t necessarily result in injuries or painful conditions. Numerous studies have been performed comparing the posture of people in pain and those without pain, and these studies have overwhelmingly found little correlation between posture and pain or dysfunction. Despite the evidence, many medical providers continue to stick to the “improve your posture” narrative when educating their patients.

One postural dysfunction that is assumed to result in pain and impaired movement is upper crossed syndrome. People classified as having upper crossed syndrome present with overstretched and weakened muscles in the upper back and back of the shoulder and tightness in the chest and front of the shoulders. This often results in thoracic kyphosis and rounded shoulders, two dysfunctions that are commonly believed to contribute to shoulder impingement and pain. One 2005 study of subacromial impingement syndrome, however, found no difference in posture between subjects with shoulder pain and those without.

Similarly, despite the fear of a forward head posture resulting in cervical disc degeneration and neck pain, this 2007 study found no significant correlation between cervical spine curvature and neck pain. The researchers in this study concluded that “when so-called ‘abnormalities’ of the sagittal profile are observed in the older patient with neck pain they must be considered coincidental, i.e. not necessarily indicative of the cause of pain.”

In the lower body, an anterior pelvic tilt (caused by tight hip flexors and weak glutes and core muscles) is often associated with increased lumbar lordosis, which is proposed to contribute to low back pain. Once again, a 2008 systematic review determined that there was no correlation between lumbar spine curvature and low back pain. On the other hand, Laird et al. found that while lumbar lordosis and angle of pelvic tilt had no effect on low back pain, those suffering from pain did demonstrate decreased lumbar range of motion and slower movement time. This is a great example of how the ability to move effectively is likely more important than posture.

Note: There is no shortage of articles, books, blog posts, podcasts, videos, and other print and online resources related to specific postural deficits, and exploring each one in detail is well beyond the scope of this post. As with anything related to research, studies can be found that present contrary views to the articles cited above. This is simply a representative selection of resources that help illustrate a larger point, that evidence to support posture as a source of pain is inconclusive, at best.

So if posture isn’t really a problem, then why should I care about it?

While there may not be a direct link between posture and injury in many cases, there are still situations when postural awareness is important.

This can be true if you are actively experiencing pain while in a static position, such as knee pain when standing at work, neck pain when working at the computer, or low back pain when trying to sleep at night. In these situations it could be useful to undergo an ergonomics assessment to determine if there are ways to modify your position and decrease pain. In some cases, static postural deficits can result in dynamic limitations – in other words an acquired decrease in range of motion or strength required to perform movement-related tasks.

Oftentimes just changing positions more frequently is enough to avoid these problems, which is why postural awareness can still be valuable. In fact, general movement and exercise may have just as much to do with decreasing pain as any “corrective exercises” that are clinically prescribed to improve posture. True changes in static posture are unlikely to occur during a standard episode of care due to the frequency, volume, and duration of exercise that would be required to offset physical adaptations to normal daily activities. Even if these changes were possible, posture is rarely objectively measured in a clinical setting anyway.

Any improvements in pain that are noted throughout a plan of care probably have less to do with achieving an ideal posture and more to do with a variety of other factors, such as effective manual therapy, activity modification to allow for proper healing of the injured area, and patient-specific movement retraining.

It’s not about “correcting” posture; it’s about finding the right fit

Studies investigating the link between posture and injury or dysfunction often focus on static posture instead of dynamic posture. One reason for this is that dynamic posture has traditionally been harder to evaluate in a research setting due to the time and resources necessary to obtain objective measurements. In some ways this renders much of the current evidence on posture irrelevant for many medical professionals, because the way that patients move is likely more predictive of injury than how they’re positioned at rest. Luckily, as technology improves and becomes more readily available, further research on dynamic posture can help guide clinical decisions.

In either case, perfect posture is difficult to normalize due to a variety of anatomical differences from one subject to the next; what may be an ideal position for one person may be detrimental to another. This is why attempting to “correct” someone’s posture based on norms is looking at the problem the wrong way. Anyone experiencing pain or limitation shouldn’t have to worry about where they fit on a normative postural curve anyway. Exercise programs should be carefully designed to help each individual adapt to the stresses that will be placed on their body, regardless of the position they’re in.

No matter what activities you perform on a daily basis, there are healthcare providers and specialists who can help you move more efficiently and find the best posture for you. Performance physical therapists like the ones found at FLO Physical Therapy are well-trained to assess your mobility, stability, and movement technique and set you on the path toward pain-free performance. Contact us today to find out more about how we can help you stay healthy and excel at the activities you love!

References:

- Czaprowski D, Stoliński Ł, Tyrakowski M, Kozinoga M, Kotwicki T. Non-structural misalignments of body posture in the sagittal plane. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2018;13:6.

- Lewis, JS, Green, A, and Wright, C. Subacromial impingement syndrome: The role of posture and muscle imbalance. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 14(4): 385-392, 2005.

- Grob, D, Frauenfelder, H, and Mannion, AF. The association between cervical spine curvature and neck pain. European Spine Journal 16(5): 669-678, 2007.

- Christensen, ST, and Hartvigsen, J. Spinal curves and health: a systematic critical review of the epidemiological literature dealing with associations between sagittal spinal curves and health. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics 31(9): 690-714, 2008.

- Laird RA, Gilbert J, Kent P, Keating JL. Comparing lumbo-pelvic kinematics in people with and without back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:229.

- Hrysomallis, C, and Goodman, C. A review of resistance exercise and posture realignment. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 15(3):385-399, 2001.